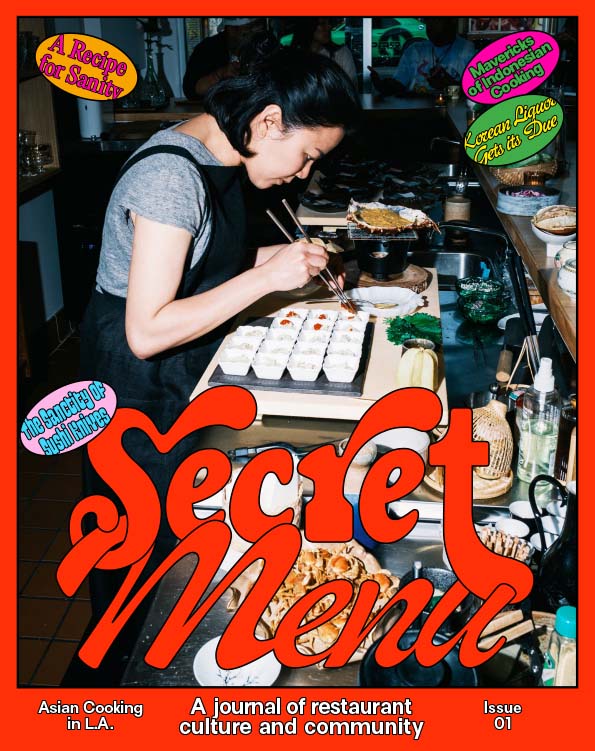

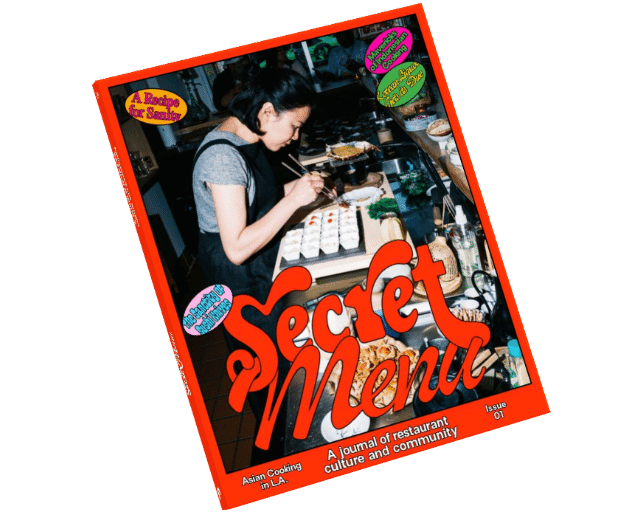

Letter From the Editors

Introduction

Lisa Ling on why Asian food in Los Angeles matters.

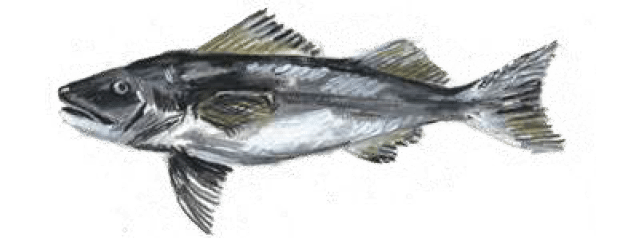

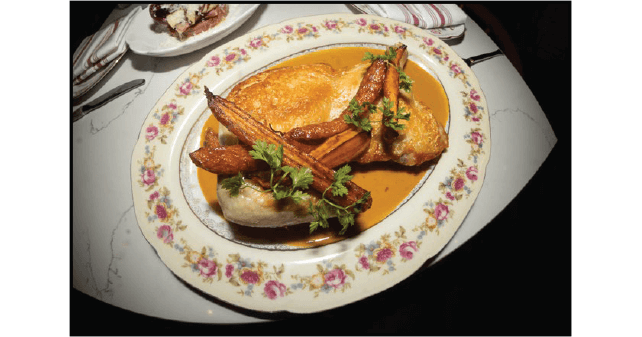

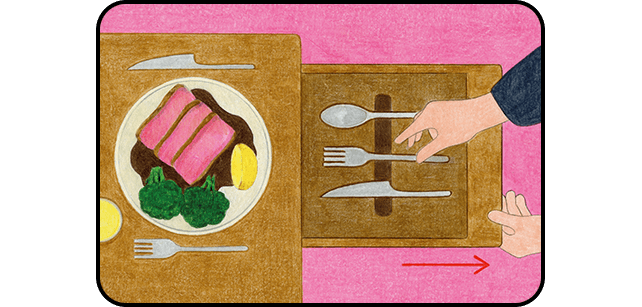

From Sea to Table

A black cod goes from the Pacific to Shibumi.

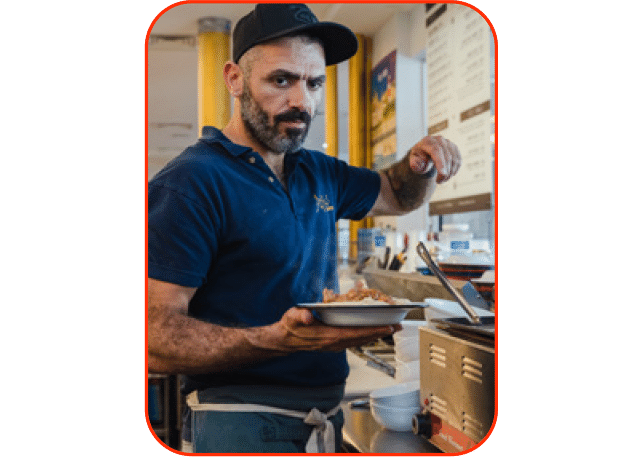

Recipe for Sanity

Keeping cool when the kitchen gets hot.

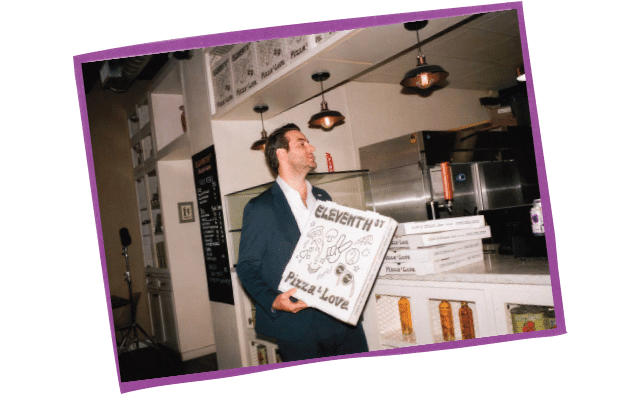

Threading the Needle

One restaurant’s many pandemic pivots.

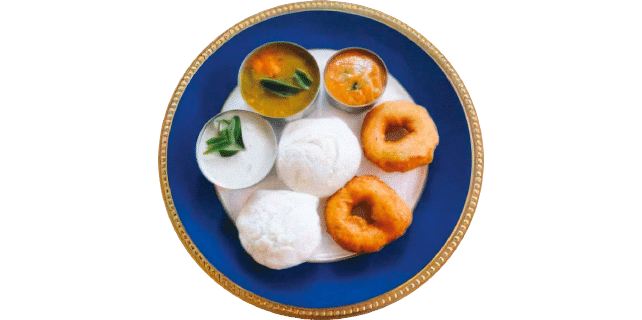

The Original and The Remix

Two different takes on Indian food.

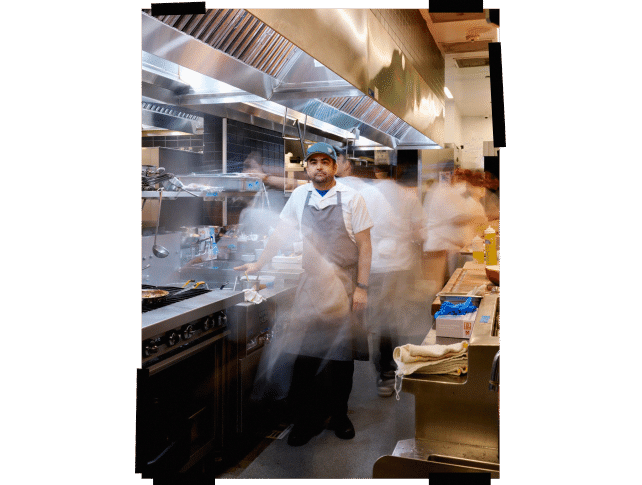

(S)woon!

Every day’s a hustle at Woon.

Harvesting Heritage

From Asian farms to Los Angeles restaurants.

Hail, Hail, Beloved Strip Mall

Why in L.A. they’re not boring.

Never Mind the Rules

Three restaurants breaking boundaries.

Sustainably Minded

Mastering values at Yang’s Kitchen.

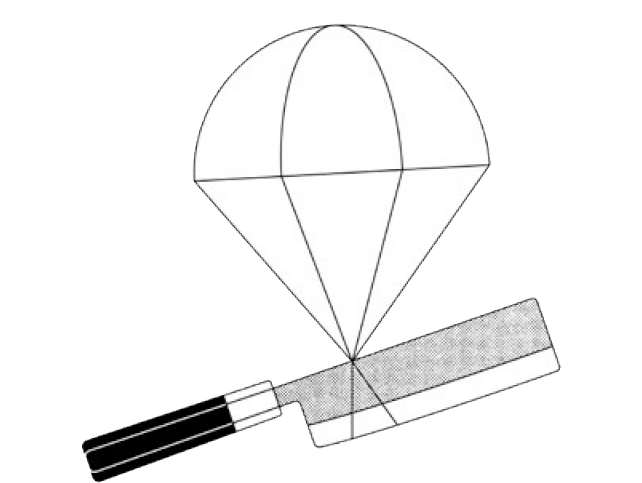

The Sanctity of Sushi Knives

Two chefs go behind the blade.

Renegades Next Door

Omakase and ramen join the neighborhood.

Korean Liquor Gets Its Due

The coronation of soju and makgeolli.

Drinking at Genever

Three women open the bar they want to walk into.

Island Hopping In Los Angeles

Indonesian community through cuisine.

All Together Now

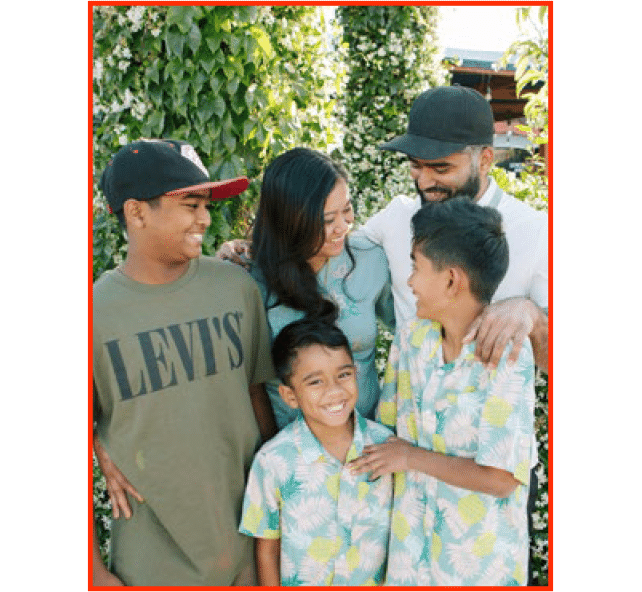

On working with Mom and Dad at Anajak Thai.

Cat Food

Los Angeles before sushi.

Family Meal

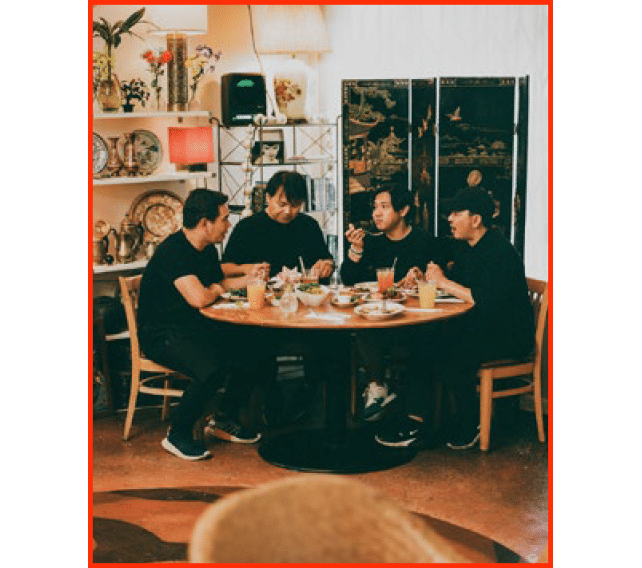

Inside the staff ritual of eating together.

Forget About Pho

Three Vietnamese restaurants expand the city’s palate.

Where’s the Filipino Food?

One chef has some thoughts.

At Home Away from Home

Waking up Los Angeles to Burmese cuisine.

Room to Grow

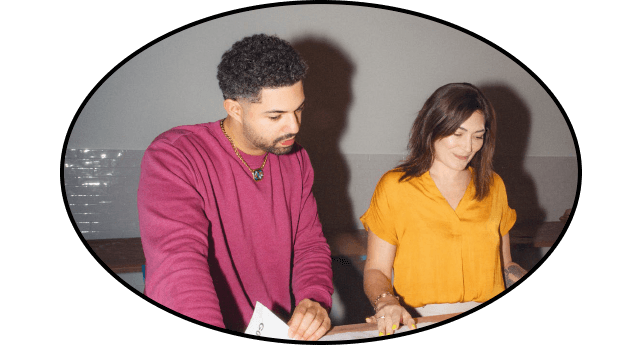

The couple behind Shiku goes with the flow.

Running a Restaurant is Hard AF

An ode to those who keep them going.

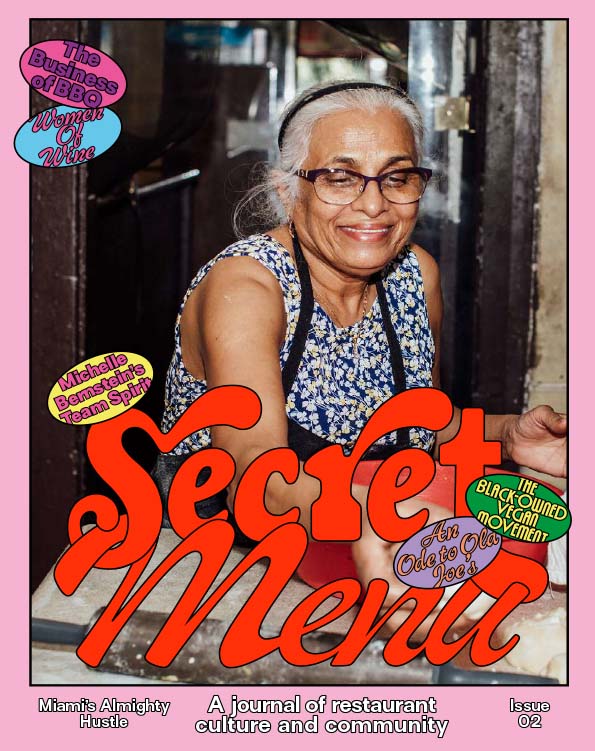

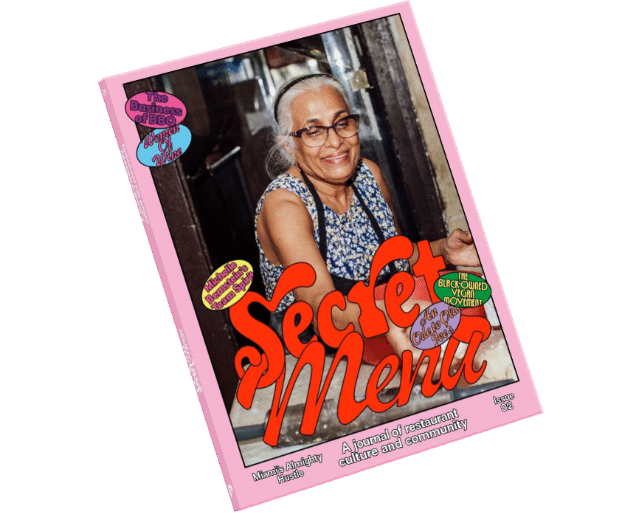

Letter From the Editors

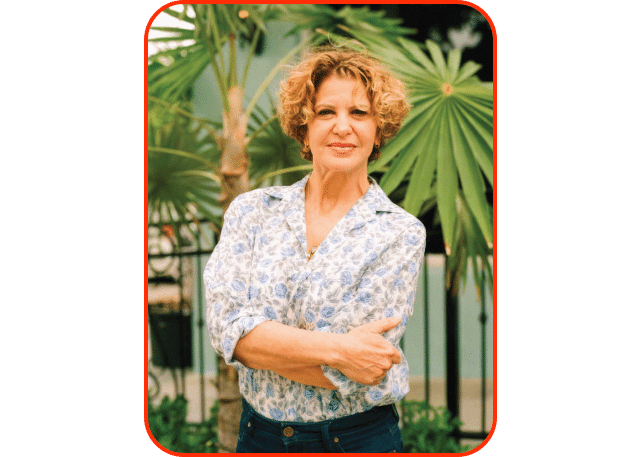

Bring It

Michelle Bernstein embraces the competition.

From Red to Black

One restaurant’s epic journey from debt to success.

That’s Amore

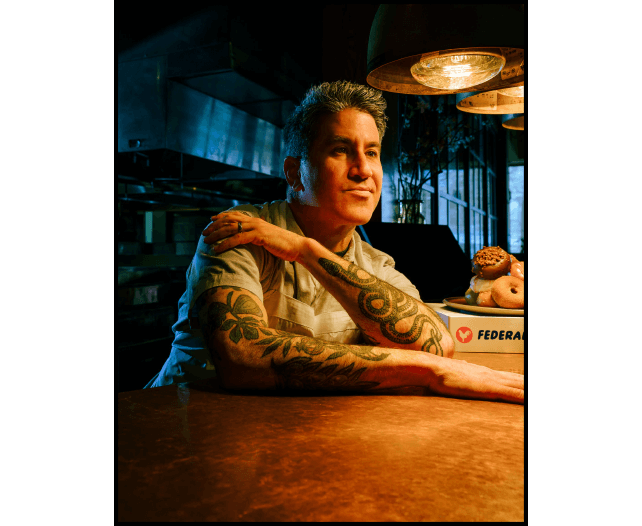

The couple behind Boia De and Walrus Rodeo play by their own rules.

Buzzworthy

Vermouth gets a bar of its own.

The Keepers Of The Flame

On the business of BBQ in Miami.

The Cost Of Doing Business

Recipes for navigating an uncertain economy.

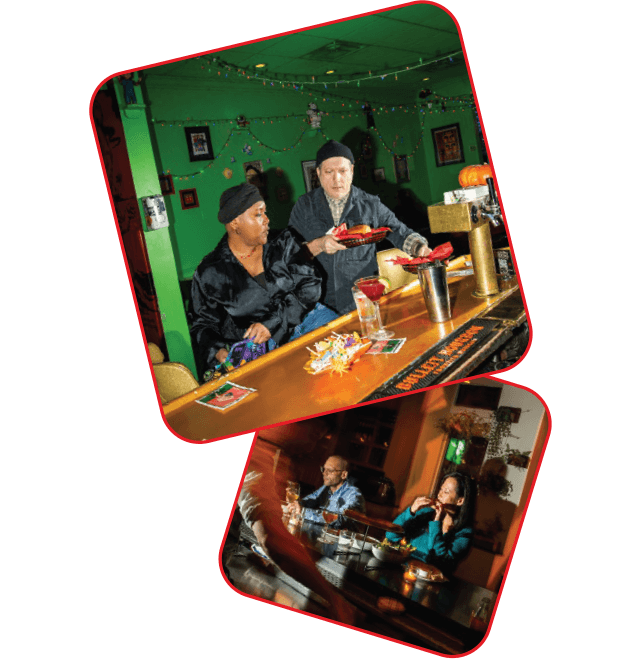

An Ode To Old Joe’s

The secret to never getting old in a town obsessed with what’s new.

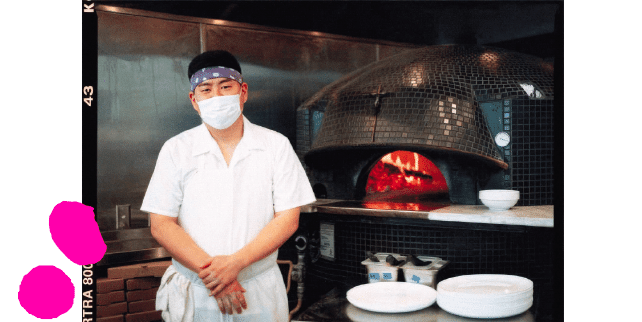

In Toro We Trust

How two pioneers of omakase introduced Miami to a new way of dining out.

Do You Know The Masa Man?

Chasing a childhood memory one arepa at a time.

More Than A Meal

Why Miami’s mainstays of Middle Eastern food aren’t phased by the influx of glossy newcomers.

The Chameleon

David Foulquier on his shapeshifting ambitions.

Our Community Deserves This.

The Black chefs behind a vegan movement in Miami.

The Great Sandwich Summit

Two Cuban sandwich masters talk shop.

In Search Of Lox Time

A new generation’s take on the classic Jewish deli.

Well Grounded In The Magic City

Miami’s mavericks of sustainable growing and dining.

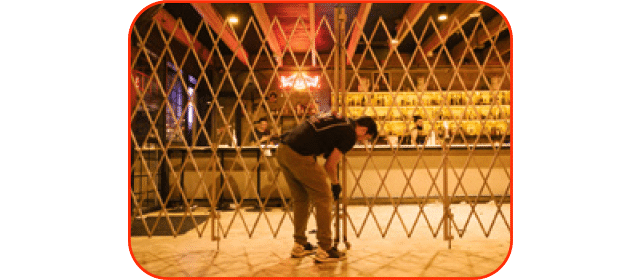

Closing Time

An intimate glimpse inside restaurants after the last customer leaves.

Dream Team

Creating a culture where employees stick around.

Women Of Wine

A new kind of bottle service takes root in Miami.

Holding It Down

The art of staying put in a changing city.

Windows Into Miami

The city’s ventanitas created a culture all their own.

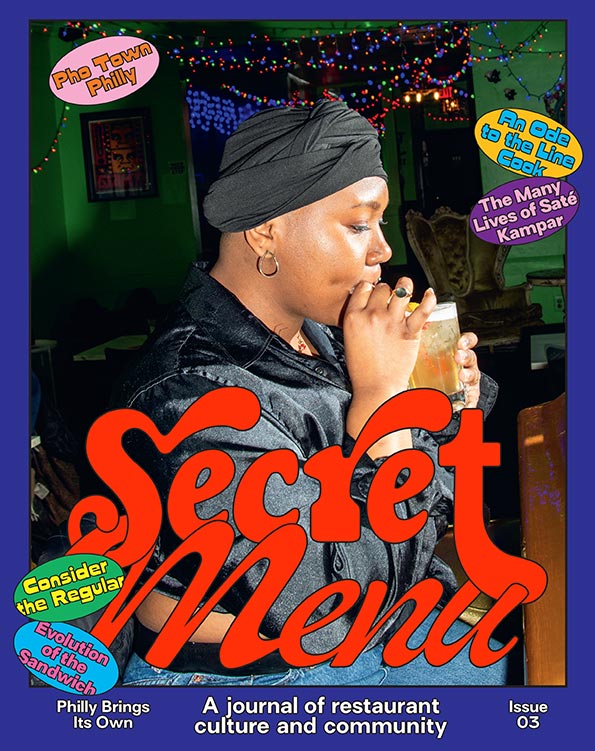

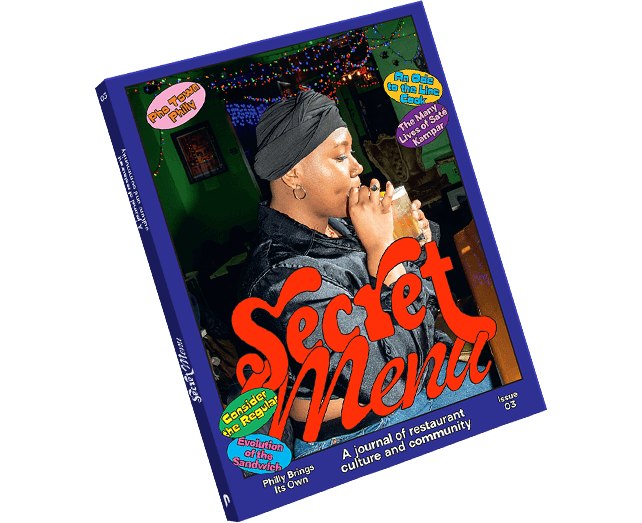

Letter From the Editors

Everybody Likes Us, We Don’t Care

Philadelphia Magazine’s food critic on the irrepressible attitude that is the key ingredient of the city’s restaurants.

Vetri’s Family

How one restaurant gave birth to many.

Plant to Plate

The cheesesteak may be the global mascot of Philly. But a contingent of pioneering chefs and restaurateurs have made the city a hub of vegetarian innovation.

Come One, Come All!

The city’s Eritrean-Ethiopian restaurants serve up more—way more—than delicious food.

The Breadwinner

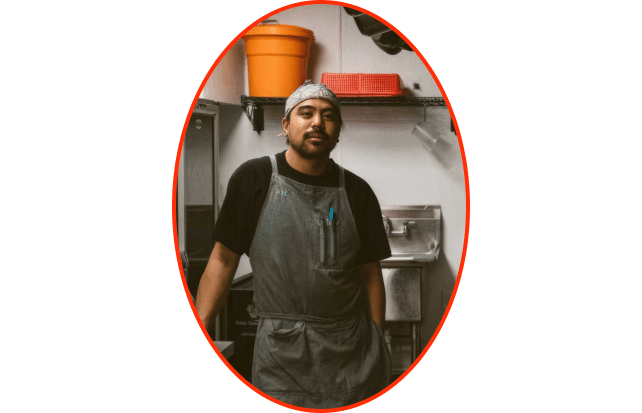

How Juan Carlos Aparicio baked his way to running a restaurant (that isn’t a bakery).

What’s the Frequency, Alex?

How Alex Tewfik went from being a food editor in Philly to owning one of the best restaurants in town.

On a Mission

Two restaurants that share a belief in how cooking can be force for change.

The Ambassador of Spice

How Chutatip Suntaranon channeled her upbringing in Thailand—and life spent flying around the world—into one of Philly’s most singular restaurants.

Make It On Our Own

Stopping by the warehouses in Kensington where artisan upstarts are breathing new life into the city’s food scene.

Survival of the Tastiest

The Ongoing Evolution of Philly’s Classic Sandwiches.

Break On Through

Chloé Grigri, Amanda Shulman, and Ellen Yin on upending the rules of the game.

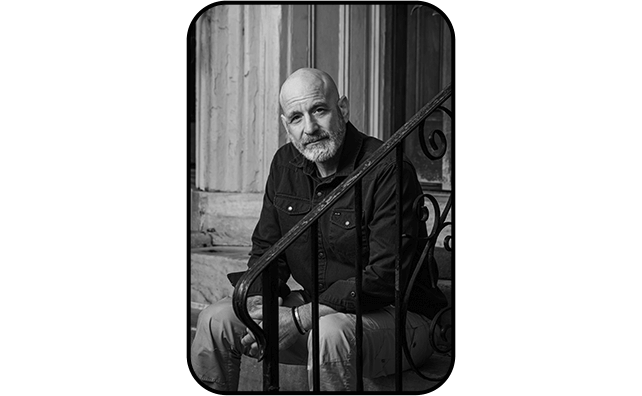

Plan Z

Mike Solomonov takes stock of his journey.

The Regulars

When a customer becomes a friend.

The Many Lives of Saté Kampar

Ange Branca was forced to close her beloved restaurant in 2020. That was just the beginning.

Everything Old is New Again

How do you build a restaurant in a space that was never meant for a restaurant? In Philly, a city of Revolutionary Warera buildings and colonial row houses and ancient warehouses, it can be a bit like playing Tetris with Benjamin Franklin.

The Dish on Love

Three Philly couples get frank and intimate in sharing their recipes for romance.

Your Place or Mine?

Inside the world of homespun pop-ups and unexpected collaborations that have made Philly’s dining scene like nowhere else.

Wild Spirits

The classics are easy enough to master by anyone with fine liquor and a recipe.

Photown Philly

The city has long been a vibrant hub of Vietnamese food. Today, a new generation is striking a balance all their own—between creativity and tradition, innovation and memory.

Lessons On the Line

An ode to the unsung heroes of restaurant kitchens from a comedy writer who couldn’t take the heat.

Advice to Your Younger Self

A cell phone has been invented that allows you to send one text message to your younger self. What do you write?